Idealism in Context

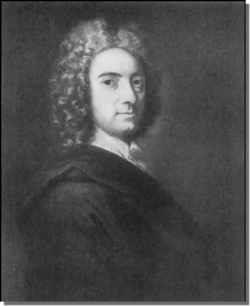

Abstract: The idealist philosophy of Bishop George Berkeley (pictured left) should be reinterpreted not as an outmoded metaphysical theory, but as a philosophically astute protest against the “great abstraction” initiated by the scientific revolution — a defense of the primacy of experience and the indispensability of the observer, in a historical moment when knowledge was being severed from consciousness in favor of a disembodied ‘view from nowhere’.

The Philosopher of the Immaterial

George Berkeley (1685–1753) was an Irish philosopher and Anglican bishop best known for his philosophy of immaterialism — the view that physical objects exist only if perceived (summed up in the memorable aphorism ‘esse est percipi’). Though sometimes dismissed as an eccentric for denying the reality of matter, Berkeley was in reality a rigorous and highly influential thinker, engaging deeply with the scientific and philosophical debates of his time. His works display sharp reasoning, lucid prose, and a deep insight into the limits of human knowledge. Influential philosophers such as David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and even modern cognitive scientists have taken his arguments seriously, whether to extend them or to refute them. Far from being a marginal figure, Berkeley stands as one of the great philosophers, grappling with many of the same problems that remain central today.

So, Does a Tree fall in the Forest?

George Berkeley’s central philosophical claim is that to be is to be perceived (esse est percipi). He denies the existence of mind-independent matter — not the reality of the world itself, but the idea that it exists apart from perception. According to Berkeley, all sensible objects — colors, sounds, shapes, and so on — exist only insofar as they are perceived by a mind. (This is the subject of the philosophical riddle, if a tree falls in the forest when nobody is there to see it, does it really fall?) Berkeley says what we call the “external world” consists of ideas within the minds of observers, and ultimately within the divine mind of God, who guarantees the continuity and coherence of experience. Berkeley was keen to stress that he did not deny the reality of the world as such. In his own words:

I do not argue against the existence of any one thing that we can apprehend, either by sense or reflection. That the things I see with my eyes and touch with my hands do exist, really exist, I make not the least question. The only thing whose existence we deny is that which philosophers call ‘matter’ or ‘corporeal substance’. ¹*

What Berkeley objected to was the notion — rooted in Galileo's division of primary and secondary qualities — that reality consists of a material substance existing apart from perception, an abstraction he believed explained nothing and sowed the seeds of skepticism. His philosophy was intended as a corrective to this, affirming instead that the world is as it appears to us in experience — vivid, structured, and meaningful, but always in relation to a mind (although, importantly for Berkeley, the mind of God served as a kind of universal guarantor of reality, as by Him all things are perceived, and so maintained in existence).

Idealism Redux

With the benefit of hindsight, at least some of Berkeley’s philosophy remains plausible. In On Physics and Philosophy (2006), Physicist Bernard d’Espagnat invoked George Berkeley — not to outright endorse his philosophy, but to acknowledge that quantum theory challenges the assumption of a mind-independent reality ². Paradoxically, a scientific revolution formerly anticipated as the culmination of realism ends up reviving precisely the kind of questions that Berkeley posed in the early 18th century!

D’Espagnat recognizes the enduring relevance of Berkeley’s line of inquiry: What is the ontological status of the unobserved? Can we meaningfully speak of a world existing wholly apart from perception? Resolutions to these questions remain surprisingly elusive.

As d’Espagnat famously observed, quantum physics suggests that “reality is not wholly real” in the sense assumed by scientific realism. In this, it echoes — even if it does not replicate — Berkeley’s insight that the so-called external world may lack an ontological ground outside of perception. For both thinkers, in very different contexts, the role of the observer — whether as ‘mind’ or ‘spirit’ in Berkeley, or as measurement and observation in quantum physics — proves central. Indeed, the apparent indispensability of the observer (or at least the act of measurement), has become a pivotal philosophical issue in contemporary physics.

The Matter with Matter

We noted above that what Berkeley denies is not the reality of the objects of sense, but of material substance — something which underlies and stands apart from the objects it comprises. Much ink has been and can be spilled on this question, but the point of this essay is to situate Berkeley’s objection to substance in its historical context.

The earlier philosophy of Aquinas, building on Aristotle, maintained that true knowledge arises from a real union between knower and known. As Aristotle put it, “the soul (psuchē) is, in a way, all things,”⁶ meaning that the intellect becomes what it knows by receiving the form of the known object. Aquinas elaborated this with the principle that “the thing known is in the knower according to the mode of the knower.” ⁷ In this view, to know something is not simply to construct a mental representation of it, but to participate in its form — to take into oneself, immaterially, the essence of what the thing is. Intellectual knowledge, unlike sensory knowledge, disengages the form of a thing from its individuating material conditions, allowing the intellect to apprehend it in its universality. This process, known as abstraction, is not merely a mental filtering but a form of participatory knowing: the intellect is conformed to the form of the particular, and that conformity gives rise to true cognition. Thus, knowledge is not an external mapping of the world but an assimilation, a union that bridges the gap between subject and object through shared intelligibility.

It is often said that Aquinas was a realist, but this should be understood in the scholastic rather than the modern sense. He affirmed the reality of universals, which modern realism does not. The idea of the world as a domain of entirely separate, independently existing objects had not yet taken hold.

This began to change in the early modern period. The word objective, in its current philosophical sense — “not dependent on the mind for existence” — entered the English lexicon in the early 17th century, during the formative era of modern science and culture. And with it came a profound shift in the way reality was understood.

The Advent of Modernity

As noted, for more traditional forms of philosophy, the real was the intelligible, and to know what is real is to participate in a cosmos imbued with meaning, value, and purpose. But in the new, scientific outlook, to be real increasingly meant to be mind-independent — and knowledge of it was understood to be obtainable in purely quantitative, mechanical terms, independently of any observer. This conceptual shift took decisive form in the work of Galileo, Descartes, and John Locke (against whom most of Berkeley’s polemics were directed). Galileo proposed that the “book of nature” is written in the language of mathematics, and that only its measurable attributes — shape, number, motion — belonged to nature herself ³. Qualities like color, taste, or warmth, by contrast, were real only in the eye of the observer. Descartes then systematized this intuition into the dualism of res extensa (extended substance, or matter) and res cogitans (thinking substance, or mind). Nature became the domain of extension and motion; mind, the domain of thought and experience.

John Locke echoed Galileo’s division with his doctrine of primary and secondary qualities: the former (solidity, extension, number, motion) were intrinsic to objects; the latter (color, sound, taste) were the result of subjective experience⁴. In this view, “objective reality” is what remains when all the qualities contributed by the mind are stripped away. So, from the participatory knowledge of the Medievals, in this development, the domains of the objective and subjective became utterly separated (a conundrum which Descartes himself recognised but was never able to really solve).

But this conceptual division, for all the scientific power it was to deliver, came at a cost. As Husserl would much later argue in The Crisis of European Sciences⁵, it negates the role of the subject — the experiencing, meaning-giving mind — by treating reality as though it could be fully understood apart from any subject— a subject to whom it means something. Ancient geometry, Husserl observed, dealt with finite and concrete tasks, rooted in the intuitive understanding of forms, represented in classical architecture. Modern science, by contrast, generated a “rational, infinite totality of being,” where the world is modeled not as it is lived or experienced, but as it has been abstracted for quantitative analysis, and in which the subject no longer figures.

The great abstraction that Husserl critiques is precisely the one underlying the modern idea of objectivity: a mathematically tractable reality that brackets out the observer, on the grounds that the object of analysis is the same for all observers. And it is in this context that we find the origin of the modern conception of material substance — an understanding by now so deeply embedded in our culture that to question it is to be accused of ignoring reality. This is the geneology of how philosophical idealism arose in response to the disclocation introduced by the Scientific Revolution. With the advent of the new sciences, especially in the mechanistic philosophies of Galileo, Descartes, and Newton, the participatory sense of being and knowing was replaced by a dualistic one: the world becomes res extensa, a realm of extension and quantity, while the mind becomes res cogitans, the individual ego only certain of their own existence. The epistemological consequence is a representational theory of knowledge, in which the observer can only infer facts about the external world from inner ideas — an approach that severs the vital bond between mind and world.

In this analysis, idealism emerges not to deny the reality of the world, but to restore coherence and meaning by re-asserting the role of the observing mind. Importantly, there had been no need for the pre-moderns to advocate such a philosophy, because the division that idealism sought to ameliorate had not yet occured.

The Enduring Relevance of Kant

In this context, the great Immanuel Kant stands as a pivotal figure. He stands at the crossroads between early modern science and later philosophy. While he fully acknowledged the power and success of Newtonian science, he refused to reduce the human being to mere object within that system. As Emrys Westacott writes

“Kant never lost sight of the fact that while modern science is one of humanity’s most impressive achievements, we are not just knowers: we are also agents who make choices and hold ourselves responsible for our actions… But a danger carried by the scientific understanding of the world is that its power and elegance may lead us to undervalue those things that don’t count as science.”⁸

For Kant, the capacity for moral action, the experience of beauty, and the sense of wonder are not reducible to scientific description. They are constitutive of our humanity, and any philosophical account that ignores them fails to do justice to the full reality of human being.

Kant criticized Berkeley (who had preceded him) and was irritated when critics accused him of simply rehashing Berkeley’s ideas. Nevertheless there are definitely convergences between them, and both philosophers were responding, in different ways, to the same historical rupture: the advent of a conception of reality that utterly excludes the subjective dimension of existence. Without going into detail of Kant’s criticisms, the essential point is that both forms of idealism emerged as reactions to the same epochal shift in how knowledge and existence were understood in the wake of the Scientific Revolution.

Conclusion: The Displacement and Return of Idealism

In the early 20th century, philosophical idealism fell out of favor — particularly in the English-speaking world — under pressure from the rising influence of logical positivism, linguistic analysis, and a growing faith in scientific realism. It came to be regarded, often unfairly, as speculative, obsolete, or even incoherent. Yet the questions that animated idealist thought never really went away. In European philosophy, the legacy of idealism continues through phenomenology, existentialism, and constructivism. Philosophers like Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty explored in various ways the structures of experience, the situatedness of subjectivity, and the impossibility of a completely detached ‘view from nowhere.’⁹

More recently, developments in cognitive science — especially the enactivist and embodied mind approaches — have returned to questions about the relationship between perception, subjectivity, and world. These frameworks reject the idea of a passive mind merely representing a pre-given reality, and instead emphasize the co-constitution of mind and world through embodied activity.

In this way, the concerns of idealism re-emerge, not as nostalgic metaphysics, but as a vital part of understanding what it means to experience, to know, and to be — the core concerns of philosophy, if not always of science. Bernardo Kastrup¹⁰ has emerged as an articulate defender of philosophical idealism, and idealism retains a place at the table, in dialogue with the various other schools and trends in modern philosophical thought.

But to understand why idealism is important, we need to be clear about what prompted its emergence in the early modern period, and what about it remains relevant. That is what I hope this brief essay has introduced.

#philosophy #Idealism #HistoryOfScience #Epistemology

Bibliography and References

- Berkeley, George. Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous, edited by Robert M. Adams, Hackett Publishing, 1979.

- d’Espagnat, Bernard. On Physics and Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Galileo Galilei, Il Saggiatore (The Assayer), 1623. Translation from Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, ed. Stillman Drake, Anchor Books, 1957.

- John Locke. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, edited by Peter H. Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), II.viii.9.

- Edmund Husserl. The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy, trans. David Carr (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970)

- Aristotle, De Anima, III.8, 431b21. Trans. Hugh Lawson-Tancred (London: Penguin Classics, 1986)

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I, q. 12, a. 4. Trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (New York: Benziger Bros., 1947)

- Westacott, Emrys. ~The Continuing Relevance of Immanuel Kant~ (retrieved 1 July 2025)

- Nagel, Thomas. The View from Nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Bernardo Kastrup, Analytical Idealism in a Nutshell (Hants, UK: Iff Books, 2022).